Description

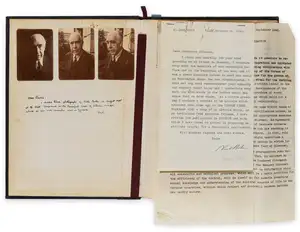

Newton (Sir Isaac) Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, 3 parts in 1, first edition, presentation copy to Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and with his ink and pencil annotations, title printed in red and black, 19 folding engraved plates, paper flaw to part 1 p.98 with some distortion to 2 lines of text and letters supplied in ink by the printer, a couple of other printing flaws probably features of the earliest copies to come off the press, contemporary panelled calf, rubbed, joints split but firm, spine ends slightly chipped, corners worn, lacking spine label, preserved in modern silk-lined green morocco drop-back box by Shepherds, [Babson p.66; Gray 174; Wallis 174], 4to, Printed for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford, Printers to the Royal Society, 1704.

⁂ Highly important association copy, received by Fatio, Newton's close friend and collaborator, five days before Newton himself presented a copy to the Royal Society. The earliest known presentation copy of the only book Newton prepared for publication and saw through the press himself.

Inscribed at the top of the front pastedown in Fatio's hand: 'Ex Dono Autoris Clarissimi: Londini, Februarii undecimo, 1703/4. Nicolaus Facius.' Fatio also used the Latin form of his name in an inscription recording presentation by Newton in his copy of the third edition of the Principia (1726).

The date of presentation is of particular interest. The Opticks builds on work that Newton carried out as early as the mid-1660s and later presented in his earliest lectures as Lucasian Professor in Cambridge. His first publications in the journal of the Royal Society, the Philosophical Transactions, were on the nature of light. For much of the 1670s, he engaged in critical correspondence with English and Continental virtuosi about his findings. As he stated in the 'Advertisement' at the beginning of the published Opticks, he began to prepare a more complete work on light in about 1675. He returned to the idea of publishing this work only after the appearance of the Principia (which contained one section on optical mechanics) in 1687 had won him international fame. The manuscript was largely prepared in the period 1687-8 and 1691-2. The Scottish mathematician and Oxford Professor of Astronomy, David Gregory, saw an incomplete text when he visited Newton in Cambridge in May 1694. Newton delayed finishing the book, however, and decided to print it only in 1702 or 1703. The book was going through the press in December 1703. On 16 February 1704, Newton presented the completed book to the Royal Society, of which he had been President since 30 November 1703. The copy on offer was presented to Fatio five days earlier.

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1664-1753) was a Swiss mathematician and natural philosopher. Educated at the Academy of Geneva, Fatio worked with Giovanni Domenico Cassini at the Royal Observatory in Paris in the early 1680s. He first came to England in 1687 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society on 2 May 1688. After the Revolution of 1688, Fatio was the most important intermediary between Newton and Huygens. Fatio regarded himself (with some justification) as being among the very few mathematicians internationally who were equipped to handle the new calculus and as being in the forefront of scientists who were trying to explain the action of gravity, the force which played such an important role in the physical explanations provided by the Principia. In the early 1690s, Fatio emerged as the likeliest person to produce a revised edition of the Principia and discussed corrections to the work with Newton, to whose manuscripts he also had access. At this time, he was one of Newton's closest confidants. The two men regularly exchanged letters (several of which remain unpublished) and Fatio advised Newton in particular about the purchase of alchemical works in French.

For much of 1693, Newton and Fatio collaborated on alchemical experiments, with Fatio conveying information derived from practitioners with whom he associated in the London Huguenot community. According to William R. Newman, who has recently produced a definitive account of the alchemical collaboration of Newton and Fatio, Newton was 'testing the ability of a vitriol to "ferment" respectively with salts of lead, tin, and copper' and fermenting iron, copper, and lead with metallic quicksilver. Exhaustion from long hours tending the furnace involved in these experiments may well have caused Newton's famous breakdown, which he discussed in letters to Samuel Pepys and John Locke in autumn 1693. Newman's work demonstrates that Fatio's involvement with Newton reflected shared intellectual concerns with 'chymistry, the transformation of materials, and the production of remedies.' These interests remained vital despite Newton's illness, which cannot now be attributed to any falling out with Fatio. Fatio found new employment as a tutor in 1694, which required him to be away from London; he travelled to the Netherlands with his pupil in 1697-8, and returned to Geneva between 1699 and 1701. Nevertheless, he remained a regular participant in conversations among Newton and his disciples: his interest in the renewed editing of the Principia and in Newton's other projects was taken for granted.

In London in 1698, Fatio set to work seeing two compositions of his own through the press: an English treatise on the exploitation of the angle of the sun's rays in gardening (Fruit Walls Improved) and a Latin pamphlet on the geometrical investigation of the line of quickest descent (Lineae brevissimi descensus), a work notable for its author's attempt to reassert a position among the front rank of European mathematicians. As such Fatio was critical of the behaviour of Johann Bernoulli and his associates for the nature of the challenge problem which they had issued in 1696, and which Newton had answered with a correct solution for the line of quickest descent. Newton had presented his work anonymously in the Philosophical Transactions (January 1697), but gave no hint about the method he had followed. He presented a construction of the solution-curve (a cycloid).

Behind Bernoulli's challenge lurked Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whom Fatio accused of having ignored Newton's priority in the invention of the calculus in his publications about this mathematical tool. At the heart of the dispute lay a broader intellectual problem that many Continental mathematicians had in accepting Newton's subordination of his method of fluxions to traditional geometrical arguments and their consequent belief that Newton had not properly mastered the intricacies of the new analysis that Leibniz had developed. On such a reading, no other mathematician in England except Newton was worthy of consideration (Fatio included). Fatio's pamphlet also treated the problem of the solid of least resistance, which Newton had solved in Book II of the Principia (1687). He wished to show that, since Newton had solved the problem of the solid of least resistance in 1687, he could equally well solve the problem (belonging to the same class) of the line of quickest descent nine years later. Mathematically speaking the two problems are similar: if you know how to solve one, then you are likely to know how to solve the other. Fatio's work therefore set out to suggest that, since he and Newton had known one another and shared mathematical work since 1687, he too rightfully belonged among the sharpest mathematicians of Europe.

Fatio's publication put the cat among the pigeons and is properly considered the opening salvo in a decade and a half of philosophical warfare between Newton and Leibniz. Although Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli were critical of Fatio's own solutions to the problem of the line of quickest descent, other leading mathematicians such as Jakob Bernoulli or Jakob Hermann were far more circumspect. They were particularly interested in the explanation of the mechanism of gravity that Fatio shared with them as part of his exchanges at this time. Fatio had presented these ideas to the Royal Society as early as July 1688, but they remained topical as Continental mathematicians and philosophers struggled to interpret the Principia. In this way, Fatio's pamphlet succeeded in reclaiming attention for his own scientific ideas, as well as going into the lists for Newton's reputation. It also showed that he could handle the most difficult problems in mathematics.

By the time of his return from Switzerland in 1701, Fatio was therefore a significant player in an international debate about the nature of the calculus and about the way in which physical effects might be transmitted so as to appear to cause action at a distance. These were also concerns looked at in the Opticks, initially in the two mathematical tracts appended by Newton to the work, and later also in the queries that were developed from Newton's theory of light in the revisions made to the Latin translation (Optice) of 1706. At the same time, Fatio re-established himself as a contact between Newton and skilled craftsmen in the London Huguenot community, as is shown by exchanges between the two men in the year of publication of the Opticks. These concerned the design of watches with a jewelled mechanism, which Newton eventually tested for accuracy in December 1704. Finally, Newton was in Fatio's debt as the recipient of a presentation copy of Fatio's own publication of 1699. It is not surprising therefore to find that Fatio was one of the very first recipients of a presentation copy of the Opticks on 11 February 1704.

Newton's gift of the Opticks to Fatio and the close reading implied by Fatio's annotations formed part of a broader pattern of gift-giving. Halley presented Fatio with a copy of the first edition of the Principia in 1687 (now Bodleian Library, Oxford, shelfmark Arch. A d.37). Fatio reciprocated by presenting his own book to both Newton and Halley. Newton responded with a copy of the Opticks.

Fatio was an attentive enough reader of the mathematical treatises appended to the book to make a small number of accurate corrections which were not in the errata. The mathematical tracts appended to the Opticks included some of Newton's most profound analysis of the quadrature of curves and of cubic curves, the culmination of work that he had begun in the mid-1660s and perfected in the mid-1690s. As such they had direct relevance to the growing public quarrel into which Fatio had pitched Newton. Fatio discussed the content of the Opticks with his correspondents on the Continent, although only after the latter had been able to read the work in Latin. His ongoing interest in solar light and 'crowns of coulours wch sometimes appear about the Sun & Moon' was the subject of a letter that Newton sent to Fatio on 14 September 1724, offering to communicate his ideas to the Royal Society.

Fatio's copy of the Opticks is largely invisible in scholarship, although its possible existence is mentioned in Charles Domson's thesis 'Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and the Prophets of London' (Yale University, 1972: p. 84). Fatio died in Worcester, where he had lived since 1717, in April 1753. Half of his effects passed to Corfield Clare (d.1790), rector of Madresfield and of Alvechurch, with whom he had lodged. The other half were bequeathed to the widow of Jean Allut, who was, like Fatio, a disciple of the enthusiastic Camisard prophets who had come to England in 1706. In April 1765, the Genevan natural philosopher George-Louis Le Sage purchased for £8 some of the papers that had been left to Clare. What remained in Worcestershire was acquired by the physician and antiquary James Johnstone (c. 1730-1802). His son, John Johnstone (1768-1836), who practised medicine in Worcester from 1793, later inherited the Opticks (and made a note of its acquisition by his father on the front free endpaper). He also owned other books and papers that had belonged to Fatio (most of which are now impossible to locate). John Johnstone became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1815 and subsequently donated Fatio's notes on the revision of the Principia to the Society's library. Two books from Fatio's library (copies of the first and the third edition of the Principia) survive in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, but they had presumably been sold by either Clare or Mrs Allut immediately after Fatio's death, since they were acquired from an Oxford bookseller in 1755. The Bodleian also owns a copy of Some Manifestations and Communications of the Spirit (London, 1730), a work associated with the French Prophets, which has annotations made by Fatio in Worcester in 1731. This book belonged shortly after Fatio's death to Sir John Van Hatten of Dinton Hall, Buckinghamshire, but in the twentieth century had an American owner before being purchased by the Bodleian. The Opticks has no direct sign of provenance after John Johnstone. It does bear one or two booksellers' marks and a price (£250/0/0) indicating that it was sold in England before 1971.

The print-run of the first edition of the Opticks is unknown. From the later records in the Bowyer ledgers for other books by Newton (including the second edition of the Opticks), it seems fair to assume an edition size of between 750 and 1,000 copies. The Babson catalogue lists 35 institutional copies of the first edition of the Opticks. Wallis lists 59 with a further two (one among the Babson copies) for a supposed second issue of the Opticks from which the mathematical treatises are lacking. ESTC gives 129 institutional holdings (two of which are in fact duplicated), without differentiating the two issues. With the use of additional databases and the consultation of individual online catalogues to confirm the status of particular copies, it is straightforward to identify at least 185 surviving copies, together with one copy (from those identified by Wallis) that was destroyed in the Second World War. Of these 185 copies, it has been possible to establish provenance data and descriptions of condition for approximately thirty-five for the purposes of comparison.

Most of these copies are bound in Cambridge-style panelled calf with blind fleurons on the boards. This may reliably be assumed to have been a publisher's binding, although the spine decoration may not always have been standard (many copies have been rebacked or otherwise altered). That said, copies in unrestored, original condition (such as Edmond Halley's copy, John Locke's copy, or the copy in the Old Library of Magdalene College, Cambridge) have identical decoration, tooling, and lettering on boards, spine, and (where present) red morocco spine label (gilt lettering: NEWTON'S | OPTICKS | &c). Very few surviving copies have extensive contemporary annotations: exceptions include the copies that belonged to Newton himself (Cambridge University Library, shelfmark Adv.b.39.4, used to prepare the second edition of 1717 [lacking title-page and all after p. 137 in Book III]; Trinity College, Cambridge, shelfmark NQ.16.198 [lacking pp. 1-17 and the mathematical treatises] and McGill University Library, Montreal, MS 46 [shelfmark QC353,.N57.1704]) or the copy in the Boston Public Library (with contemporary corrections and additions not in Newton's hand, giving cross-references to the work of his Cambridge successor, William Whiston). There are a number of copies with annotations from the later eighteenth or nineteenth centuries (e.g. that at the Senate House Library, London, with the annotations of the mathematician and biographer of Newton, Augustus De Morgan).

There are also a number of copies that can be identified with provenance at or near to the date of publication. Among these is a copy bought by Francis Cremer [presumably of Ingoldisthorpe, Norfolk (d. 1759)] for 12s. in 1704, and one of the copies formerly at the Babson Institute (now on deposit in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California), which has a manuscript price code with the date 1704. Leibniz's copy (Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz Bibliothek, Hannover) was sent to him from London by John Hutton on 2 May (13 May NS) 1704 and received in Hannover via The Hague before 22 July (NS). The Opticks was published after the death of Samuel Pepys in 1703, but a copy entered his library during the period in which it was being curated by his nephew, John Jackson (before 1705). The French physician, Etienne François Geoffroy, received a copy (now in Cornell University Library), from Hans Sloane (Secretary to the Royal Society) via the Jesuit mathematician, Jean de Fontenay. Fontenay had visited London, where he presented Chinese artefacts to the Royal Society in March 1704. Geoffroy thanked Sloane for the gift in a letter of 20 January 1706 (NS) and presented a summary of the book's contents to the Académie Royale des Sciences in a series of sessions between 7 August 1706 and 1 June 1707. The first copy that can be traced as arriving in North America was given by James Peirce to the Library of Harvard College on 30 March 1706 (now in the Houghton Library).

More interesting still are copies presented to their first owners by Newton himself (none of which bear inscriptions in Newton's own hand). These include:

1. The copy now in the library of the Royal Society, presented at a meeting of the Society on 16 February 1704.

2. The copy presented by Newton to Francis Hall '[th]e beginning of March 1703' [= 1704 NS]. Since no later than 1828, this has been held by the library of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.

3. The copy presented to Edmond Halley (lot 918, Robert S. Pirie sale, Sotheby's New York 2015). This is inscribed by Halley 'Luceo' and (perhaps not in Halley's hand) 'Ex dono doctissimi Authoris'. It is in a similar binding to the copy on offer here, but with the red morocco label present. It measures 24.5 cm x 16.6 cm, so is marginally taller (but less wide) that Fatio's copy.

4. The copy given by Newton to John Locke (died 28 October 1704), now in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. It is inscribed by Locke: 'Ex dono Auctoris | Viri Doctissimi. Intigerrimi Amicissimi' and was given to Trinity in 1895. The first of the corrections in the errata is made in ink; Rr1v and Rr4r are poorly printed. It is in a similar binding to the copy on offer here, but with the red morocco label present. It is slightly taller and wider than Fatio's copy, suggesting that despite the similarities in binding there were distinctions made by the binder between larger and ordinary, smaller copies for presentation.

5. The copy (now lost) that Newton sent to the Pisan mathematician, Guido Grandi (1671-1742), accompanied by a letter dated 26 May 1704. This copy cannot be located among Grandi's books in the manuscript catalogue of his library prepared in 1769, and precise details about it are therefore unknown. The library has been part of the Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa since 1783. A copy of the 1706 Optice may be found there.

6. The copy offered at Christie's New York on 16 June 2016 (lot 131), which bears the inscription 'Ex dono Authoris Mathematicorum Coryphaei, 1703/4'.

Many of Fatio's annotations deal with errors already described on the errata page of the Opticks (where Fatio notes that he has corrected these errata in the text: "Haec Errata correcta sunt'). Most are in ink, some are in pencil. The pencil corrections, which are confined to De Quadratura, are all found in the 1711 edition of Newton's mathematical tracts and were presumably added after that date. The ink corrections are more likely to have been made shortly after Fatio was given the book, although some of them may have been incorporated from the 1706 Latin Optice, in which they also appear. There is no evidence of any communication between Newton and Fatio in the making of these corrections. The only one of Newton's copies of the Opticks to contain the mathematical tracts is now at McGill University. It contains only one of the corrections made by Fatio in pencil, but it also contains many other corrections and additions incorporated either in the 1706 Optice or in the 1711 mathematical tracts which are not in Fatio's copy of the Opticks. The errata are mostly corrected in the main body of the text in all three of Newton's copies of the Opticks. In the copy at Trinity College, these corrections are frequently not in Newton's hand, suggesting that they were made already in the printing shop. In Fatio's copy, occasional items in the errata have not been corrected in the text (e.g. the corrections for pp. 86, 93, and one of those for p. 143 in book I, pp. 11 (in fact, a mistake in the errata); pp. 96, 101 (where the wrong number is corrected by Fatio) in book II). Despite such slips, the annotations show Fatio as an attentive and mathematically literate reader of the Opticks.

This copy is the earliest witness to the publication of the Opticks and a valuable testament to the ongoing friendship and intellectual exchange between Newton and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a very significant figure in his own right and the first mover in the public calculus controversy. It is one of only four books known from Fatio's library and is undoubtedly the most significant book that could emerge that he owned. It is a more interestingly annotated copy of the Opticks than any of the other surviving presentation copies (including that given to Halley) or than most of the other copies (apart from Newton's own) with contemporary annotations and provenance. Of known presentation copies that cannot now be located, Grandi's would not compare with Fatio's for interest or significance, Other copies that might be presumed to have existed include that of John Flamsteed (acquired by November 1704, but unknown apart from references in correspondence) and that of David Gregory. Because the book was in English, most important Continental contemporaries of Newton (such as the Bernoullis) did not acquire it until after the publication of the Latin Optice in 1706. None of these copies, were they to come onto the market, would surpass Fatio's unless they were very heavily annotated with original material. Moreover, Fatio's copy is in good, original condition and compares very well in this respect with any other copy that is available or likely to become available.

We are extremely grateful to Scott Mandelbrote for his help in cataloguing this lot.

Lot 290

Newton (Sir Isaac) Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, first edition, presentation copy to Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and with his ink and pencil annotations, Printed for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford, Printers to the Royal Society, 1704.

Hammer Price: £155,000

Description

Newton (Sir Isaac) Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, 3 parts in 1, first edition, presentation copy to Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and with his ink and pencil annotations, title printed in red and black, 19 folding engraved plates, paper flaw to part 1 p.98 with some distortion to 2 lines of text and letters supplied in ink by the printer, a couple of other printing flaws probably features of the earliest copies to come off the press, contemporary panelled calf, rubbed, joints split but firm, spine ends slightly chipped, corners worn, lacking spine label, preserved in modern silk-lined green morocco drop-back box by Shepherds, [Babson p.66; Gray 174; Wallis 174], 4to, Printed for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford, Printers to the Royal Society, 1704.

⁂ Highly important association copy, received by Fatio, Newton's close friend and collaborator, five days before Newton himself presented a copy to the Royal Society. The earliest known presentation copy of the only book Newton prepared for publication and saw through the press himself.

Inscribed at the top of the front pastedown in Fatio's hand: 'Ex Dono Autoris Clarissimi: Londini, Februarii undecimo, 1703/4. Nicolaus Facius.' Fatio also used the Latin form of his name in an inscription recording presentation by Newton in his copy of the third edition of the Principia (1726).

The date of presentation is of particular interest. The Opticks builds on work that Newton carried out as early as the mid-1660s and later presented in his earliest lectures as Lucasian Professor in Cambridge. His first publications in the journal of the Royal Society, the Philosophical Transactions, were on the nature of light. For much of the 1670s, he engaged in critical correspondence with English and Continental virtuosi about his findings. As he stated in the 'Advertisement' at the beginning of the published Opticks, he began to prepare a more complete work on light in about 1675. He returned to the idea of publishing this work only after the appearance of the Principia (which contained one section on optical mechanics) in 1687 had won him international fame. The manuscript was largely prepared in the period 1687-8 and 1691-2. The Scottish mathematician and Oxford Professor of Astronomy, David Gregory, saw an incomplete text when he visited Newton in Cambridge in May 1694. Newton delayed finishing the book, however, and decided to print it only in 1702 or 1703. The book was going through the press in December 1703. On 16 February 1704, Newton presented the completed book to the Royal Society, of which he had been President since 30 November 1703. The copy on offer was presented to Fatio five days earlier.

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1664-1753) was a Swiss mathematician and natural philosopher. Educated at the Academy of Geneva, Fatio worked with Giovanni Domenico Cassini at the Royal Observatory in Paris in the early 1680s. He first came to England in 1687 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society on 2 May 1688. After the Revolution of 1688, Fatio was the most important intermediary between Newton and Huygens. Fatio regarded himself (with some justification) as being among the very few mathematicians internationally who were equipped to handle the new calculus and as being in the forefront of scientists who were trying to explain the action of gravity, the force which played such an important role in the physical explanations provided by the Principia. In the early 1690s, Fatio emerged as the likeliest person to produce a revised edition of the Principia and discussed corrections to the work with Newton, to whose manuscripts he also had access. At this time, he was one of Newton's closest confidants. The two men regularly exchanged letters (several of which remain unpublished) and Fatio advised Newton in particular about the purchase of alchemical works in French.

For much of 1693, Newton and Fatio collaborated on alchemical experiments, with Fatio conveying information derived from practitioners with whom he associated in the London Huguenot community. According to William R. Newman, who has recently produced a definitive account of the alchemical collaboration of Newton and Fatio, Newton was 'testing the ability of a vitriol to "ferment" respectively with salts of lead, tin, and copper' and fermenting iron, copper, and lead with metallic quicksilver. Exhaustion from long hours tending the furnace involved in these experiments may well have caused Newton's famous breakdown, which he discussed in letters to Samuel Pepys and John Locke in autumn 1693. Newman's work demonstrates that Fatio's involvement with Newton reflected shared intellectual concerns with 'chymistry, the transformation of materials, and the production of remedies.' These interests remained vital despite Newton's illness, which cannot now be attributed to any falling out with Fatio. Fatio found new employment as a tutor in 1694, which required him to be away from London; he travelled to the Netherlands with his pupil in 1697-8, and returned to Geneva between 1699 and 1701. Nevertheless, he remained a regular participant in conversations among Newton and his disciples: his interest in the renewed editing of the Principia and in Newton's other projects was taken for granted.

In London in 1698, Fatio set to work seeing two compositions of his own through the press: an English treatise on the exploitation of the angle of the sun's rays in gardening (Fruit Walls Improved) and a Latin pamphlet on the geometrical investigation of the line of quickest descent (Lineae brevissimi descensus), a work notable for its author's attempt to reassert a position among the front rank of European mathematicians. As such Fatio was critical of the behaviour of Johann Bernoulli and his associates for the nature of the challenge problem which they had issued in 1696, and which Newton had answered with a correct solution for the line of quickest descent. Newton had presented his work anonymously in the Philosophical Transactions (January 1697), but gave no hint about the method he had followed. He presented a construction of the solution-curve (a cycloid).

Behind Bernoulli's challenge lurked Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whom Fatio accused of having ignored Newton's priority in the invention of the calculus in his publications about this mathematical tool. At the heart of the dispute lay a broader intellectual problem that many Continental mathematicians had in accepting Newton's subordination of his method of fluxions to traditional geometrical arguments and their consequent belief that Newton had not properly mastered the intricacies of the new analysis that Leibniz had developed. On such a reading, no other mathematician in England except Newton was worthy of consideration (Fatio included). Fatio's pamphlet also treated the problem of the solid of least resistance, which Newton had solved in Book II of the Principia (1687). He wished to show that, since Newton had solved the problem of the solid of least resistance in 1687, he could equally well solve the problem (belonging to the same class) of the line of quickest descent nine years later. Mathematically speaking the two problems are similar: if you know how to solve one, then you are likely to know how to solve the other. Fatio's work therefore set out to suggest that, since he and Newton had known one another and shared mathematical work since 1687, he too rightfully belonged among the sharpest mathematicians of Europe.

Fatio's publication put the cat among the pigeons and is properly considered the opening salvo in a decade and a half of philosophical warfare between Newton and Leibniz. Although Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli were critical of Fatio's own solutions to the problem of the line of quickest descent, other leading mathematicians such as Jakob Bernoulli or Jakob Hermann were far more circumspect. They were particularly interested in the explanation of the mechanism of gravity that Fatio shared with them as part of his exchanges at this time. Fatio had presented these ideas to the Royal Society as early as July 1688, but they remained topical as Continental mathematicians and philosophers struggled to interpret the Principia. In this way, Fatio's pamphlet succeeded in reclaiming attention for his own scientific ideas, as well as going into the lists for Newton's reputation. It also showed that he could handle the most difficult problems in mathematics.

By the time of his return from Switzerland in 1701, Fatio was therefore a significant player in an international debate about the nature of the calculus and about the way in which physical effects might be transmitted so as to appear to cause action at a distance. These were also concerns looked at in the Opticks, initially in the two mathematical tracts appended by Newton to the work, and later also in the queries that were developed from Newton's theory of light in the revisions made to the Latin translation (Optice) of 1706. At the same time, Fatio re-established himself as a contact between Newton and skilled craftsmen in the London Huguenot community, as is shown by exchanges between the two men in the year of publication of the Opticks. These concerned the design of watches with a jewelled mechanism, which Newton eventually tested for accuracy in December 1704. Finally, Newton was in Fatio's debt as the recipient of a presentation copy of Fatio's own publication of 1699. It is not surprising therefore to find that Fatio was one of the very first recipients of a presentation copy of the Opticks on 11 February 1704.

Newton's gift of the Opticks to Fatio and the close reading implied by Fatio's annotations formed part of a broader pattern of gift-giving. Halley presented Fatio with a copy of the first edition of the Principia in 1687 (now Bodleian Library, Oxford, shelfmark Arch. A d.37). Fatio reciprocated by presenting his own book to both Newton and Halley. Newton responded with a copy of the Opticks.

Fatio was an attentive enough reader of the mathematical treatises appended to the book to make a small number of accurate corrections which were not in the errata. The mathematical tracts appended to the Opticks included some of Newton's most profound analysis of the quadrature of curves and of cubic curves, the culmination of work that he had begun in the mid-1660s and perfected in the mid-1690s. As such they had direct relevance to the growing public quarrel into which Fatio had pitched Newton. Fatio discussed the content of the Opticks with his correspondents on the Continent, although only after the latter had been able to read the work in Latin. His ongoing interest in solar light and 'crowns of coulours wch sometimes appear about the Sun & Moon' was the subject of a letter that Newton sent to Fatio on 14 September 1724, offering to communicate his ideas to the Royal Society.

Fatio's copy of the Opticks is largely invisible in scholarship, although its possible existence is mentioned in Charles Domson's thesis 'Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and the Prophets of London' (Yale University, 1972: p. 84). Fatio died in Worcester, where he had lived since 1717, in April 1753. Half of his effects passed to Corfield Clare (d.1790), rector of Madresfield and of Alvechurch, with whom he had lodged. The other half were bequeathed to the widow of Jean Allut, who was, like Fatio, a disciple of the enthusiastic Camisard prophets who had come to England in 1706. In April 1765, the Genevan natural philosopher George-Louis Le Sage purchased for £8 some of the papers that had been left to Clare. What remained in Worcestershire was acquired by the physician and antiquary James Johnstone (c. 1730-1802). His son, John Johnstone (1768-1836), who practised medicine in Worcester from 1793, later inherited the Opticks (and made a note of its acquisition by his father on the front free endpaper). He also owned other books and papers that had belonged to Fatio (most of which are now impossible to locate). John Johnstone became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1815 and subsequently donated Fatio's notes on the revision of the Principia to the Society's library. Two books from Fatio's library (copies of the first and the third edition of the Principia) survive in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, but they had presumably been sold by either Clare or Mrs Allut immediately after Fatio's death, since they were acquired from an Oxford bookseller in 1755. The Bodleian also owns a copy of Some Manifestations and Communications of the Spirit (London, 1730), a work associated with the French Prophets, which has annotations made by Fatio in Worcester in 1731. This book belonged shortly after Fatio's death to Sir John Van Hatten of Dinton Hall, Buckinghamshire, but in the twentieth century had an American owner before being purchased by the Bodleian. The Opticks has no direct sign of provenance after John Johnstone. It does bear one or two booksellers' marks and a price (£250/0/0) indicating that it was sold in England before 1971.

The print-run of the first edition of the Opticks is unknown. From the later records in the Bowyer ledgers for other books by Newton (including the second edition of the Opticks), it seems fair to assume an edition size of between 750 and 1,000 copies. The Babson catalogue lists 35 institutional copies of the first edition of the Opticks. Wallis lists 59 with a further two (one among the Babson copies) for a supposed second issue of the Opticks from which the mathematical treatises are lacking. ESTC gives 129 institutional holdings (two of which are in fact duplicated), without differentiating the two issues. With the use of additional databases and the consultation of individual online catalogues to confirm the status of particular copies, it is straightforward to identify at least 185 surviving copies, together with one copy (from those identified by Wallis) that was destroyed in the Second World War. Of these 185 copies, it has been possible to establish provenance data and descriptions of condition for approximately thirty-five for the purposes of comparison.

Most of these copies are bound in Cambridge-style panelled calf with blind fleurons on the boards. This may reliably be assumed to have been a publisher's binding, although the spine decoration may not always have been standard (many copies have been rebacked or otherwise altered). That said, copies in unrestored, original condition (such as Edmond Halley's copy, John Locke's copy, or the copy in the Old Library of Magdalene College, Cambridge) have identical decoration, tooling, and lettering on boards, spine, and (where present) red morocco spine label (gilt lettering: NEWTON'S | OPTICKS | &c). Very few surviving copies have extensive contemporary annotations: exceptions include the copies that belonged to Newton himself (Cambridge University Library, shelfmark Adv.b.39.4, used to prepare the second edition of 1717 [lacking title-page and all after p. 137 in Book III]; Trinity College, Cambridge, shelfmark NQ.16.198 [lacking pp. 1-17 and the mathematical treatises] and McGill University Library, Montreal, MS 46 [shelfmark QC353,.N57.1704]) or the copy in the Boston Public Library (with contemporary corrections and additions not in Newton's hand, giving cross-references to the work of his Cambridge successor, William Whiston). There are a number of copies with annotations from the later eighteenth or nineteenth centuries (e.g. that at the Senate House Library, London, with the annotations of the mathematician and biographer of Newton, Augustus De Morgan).

There are also a number of copies that can be identified with provenance at or near to the date of publication. Among these is a copy bought by Francis Cremer [presumably of Ingoldisthorpe, Norfolk (d. 1759)] for 12s. in 1704, and one of the copies formerly at the Babson Institute (now on deposit in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California), which has a manuscript price code with the date 1704. Leibniz's copy (Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz Bibliothek, Hannover) was sent to him from London by John Hutton on 2 May (13 May NS) 1704 and received in Hannover via The Hague before 22 July (NS). The Opticks was published after the death of Samuel Pepys in 1703, but a copy entered his library during the period in which it was being curated by his nephew, John Jackson (before 1705). The French physician, Etienne François Geoffroy, received a copy (now in Cornell University Library), from Hans Sloane (Secretary to the Royal Society) via the Jesuit mathematician, Jean de Fontenay. Fontenay had visited London, where he presented Chinese artefacts to the Royal Society in March 1704. Geoffroy thanked Sloane for the gift in a letter of 20 January 1706 (NS) and presented a summary of the book's contents to the Académie Royale des Sciences in a series of sessions between 7 August 1706 and 1 June 1707. The first copy that can be traced as arriving in North America was given by James Peirce to the Library of Harvard College on 30 March 1706 (now in the Houghton Library).

More interesting still are copies presented to their first owners by Newton himself (none of which bear inscriptions in Newton's own hand). These include:

1. The copy now in the library of the Royal Society, presented at a meeting of the Society on 16 February 1704.

2. The copy presented by Newton to Francis Hall '[th]e beginning of March 1703' [= 1704 NS]. Since no later than 1828, this has been held by the library of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.

3. The copy presented to Edmond Halley (lot 918, Robert S. Pirie sale, Sotheby's New York 2015). This is inscribed by Halley 'Luceo' and (perhaps not in Halley's hand) 'Ex dono doctissimi Authoris'. It is in a similar binding to the copy on offer here, but with the red morocco label present. It measures 24.5 cm x 16.6 cm, so is marginally taller (but less wide) that Fatio's copy.

4. The copy given by Newton to John Locke (died 28 October 1704), now in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. It is inscribed by Locke: 'Ex dono Auctoris | Viri Doctissimi. Intigerrimi Amicissimi' and was given to Trinity in 1895. The first of the corrections in the errata is made in ink; Rr1v and Rr4r are poorly printed. It is in a similar binding to the copy on offer here, but with the red morocco label present. It is slightly taller and wider than Fatio's copy, suggesting that despite the similarities in binding there were distinctions made by the binder between larger and ordinary, smaller copies for presentation.

5. The copy (now lost) that Newton sent to the Pisan mathematician, Guido Grandi (1671-1742), accompanied by a letter dated 26 May 1704. This copy cannot be located among Grandi's books in the manuscript catalogue of his library prepared in 1769, and precise details about it are therefore unknown. The library has been part of the Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa since 1783. A copy of the 1706 Optice may be found there.

6. The copy offered at Christie's New York on 16 June 2016 (lot 131), which bears the inscription 'Ex dono Authoris Mathematicorum Coryphaei, 1703/4'.

Many of Fatio's annotations deal with errors already described on the errata page of the Opticks (where Fatio notes that he has corrected these errata in the text: "Haec Errata correcta sunt'). Most are in ink, some are in pencil. The pencil corrections, which are confined to De Quadratura, are all found in the 1711 edition of Newton's mathematical tracts and were presumably added after that date. The ink corrections are more likely to have been made shortly after Fatio was given the book, although some of them may have been incorporated from the 1706 Latin Optice, in which they also appear. There is no evidence of any communication between Newton and Fatio in the making of these corrections. The only one of Newton's copies of the Opticks to contain the mathematical tracts is now at McGill University. It contains only one of the corrections made by Fatio in pencil, but it also contains many other corrections and additions incorporated either in the 1706 Optice or in the 1711 mathematical tracts which are not in Fatio's copy of the Opticks. The errata are mostly corrected in the main body of the text in all three of Newton's copies of the Opticks. In the copy at Trinity College, these corrections are frequently not in Newton's hand, suggesting that they were made already in the printing shop. In Fatio's copy, occasional items in the errata have not been corrected in the text (e.g. the corrections for pp. 86, 93, and one of those for p. 143 in book I, pp. 11 (in fact, a mistake in the errata); pp. 96, 101 (where the wrong number is corrected by Fatio) in book II). Despite such slips, the annotations show Fatio as an attentive and mathematically literate reader of the Opticks.

This copy is the earliest witness to the publication of the Opticks and a valuable testament to the ongoing friendship and intellectual exchange between Newton and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a very significant figure in his own right and the first mover in the public calculus controversy. It is one of only four books known from Fatio's library and is undoubtedly the most significant book that could emerge that he owned. It is a more interestingly annotated copy of the Opticks than any of the other surviving presentation copies (including that given to Halley) or than most of the other copies (apart from Newton's own) with contemporary annotations and provenance. Of known presentation copies that cannot now be located, Grandi's would not compare with Fatio's for interest or significance, Other copies that might be presumed to have existed include that of John Flamsteed (acquired by November 1704, but unknown apart from references in correspondence) and that of David Gregory. Because the book was in English, most important Continental contemporaries of Newton (such as the Bernoullis) did not acquire it until after the publication of the Latin Optice in 1706. None of these copies, were they to come onto the market, would surpass Fatio's unless they were very heavily annotated with original material. Moreover, Fatio's copy is in good, original condition and compares very well in this respect with any other copy that is available or likely to become available.

We are extremely grateful to Scott Mandelbrote for his help in cataloguing this lot.

![290

Newton (Sir Isaac) Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, 3 parts in 1, first edition, presentation copy to Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and with his ink and pencil annotations, title printed in red and black, 19 folding engraved plates, paper flaw to part 1 p.98 with some distortion to 2 lines of text and letters supplied in ink by the printer, a couple of other printing flaws probably features of the earliest copies to come off the press, contemporary panelled calf, rubbed, joints split but firm, spine ends slightly chipped, corners worn, lacking spine label, preserved in modern silk-lined green morocco drop-back box by Shepherds, [Babson p.66; Gray 174; Wallis 174], 4to, Printed for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford, Printers to the Royal Society, 1704.

*** Highly important association copy, received by Fatio, Newton's close friend and collaborator, five days before Newton himself presented a copy to the Royal Society. The earliest known presentation copy of the only book Newton prepared for publication and saw through the press himself.

Inscribed at the top of the front pastedown in Fatio's hand: 'Ex Dono Autoris Clarissimi: Londini, Februarii undecimo, 1703/4. Nicolaus Facius.' Fatio also used the Latin form of his name in an inscription recording presentation by Newton in his copy of the third edition of the Principia (1726).

The date of presentation is of particular interest. The Opticks builds on work that Newton carried out as early as the mid-1660s and later presented in his earliest lectures as Lucasian Professor in Cambridge. His first publications in the journal of the Royal Society, the Philosophical Transactions, were on the nature of light. For much of the 1670s, he engaged in critical correspondence with English and Continental virtuosi about his findings. As he stated in the 'Advertisement' at the beginning of the published Opticks, he began to prepare a more complete work on light in about 1675. He returned to the idea of publishing this work only after the appearance of the Principia (which contained one section on optical mechanics) in 1687 had won him international fame. The manuscript was largely prepared in the period 1687-8 and 1691-2. The Scottish mathematician and Oxford Professor of Astronomy, David Gregory, saw an incomplete text when he visited Newton in Cambridge in May 1694. Newton delayed finishing the book, however, and decided to print it only in 1702 or 1703. The book was going through the press in December 1703. On 16 February 1704, Newton presented the completed book to the Royal Society, of which he had been President since 30 November 1703. The copy on offer was presented to Fatio five days earlier.

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1664-1753) was a Swiss mathematician and natural philosopher. Educated at the Academy of Geneva, Fatio worked with Giovanni Domenico Cassini at the Royal Observatory in Paris in the early 1680s. He first came to England in 1687 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society on 2 May 1688. After the Revolution of 1688, Fatio was the most important intermediary between Newton and Huygens. Fatio regarded himself (with some justification) as being among the very few mathematicians internationally who were equipped to handle the new calculus and as being in the forefront of scientists who were trying to explain the action of gravity, the force which played such an important role in the physical explanations provided by the Principia. In the early 1690s, Fatio emerged as the likeliest person to produce a revised edition of the Principia and discussed corrections to the work with Newton, to whose manuscripts he also had access. At this time, he was one of Newton's closest confidants. The two men regularly exchanged letters (several of which remain unpublished) and Fatio advised Newton in particular about the purchase of alchemical works in French.

For much of 1693, Newton and Fatio collaborated on alchemical experiments, with Fatio conveying information derived from practitioners with whom he associated in the London Huguenot community. According to William R. Newman, who has recently produced a definitive account of the alchemical collaboration of Newton and Fatio, Newton was 'testing the ability of a vitriol to "ferment" respectively with salts of lead, tin, and copper' and fermenting iron, copper, and lead with metallic quicksilver. Exhaustion from long hours tending the furnace involved in these experiments may well have caused Newton's famous breakdown, which he discussed in letters to Samuel Pepys and John Locke in autumn 1693. Newman's work demonstrates that Fatio's involvement with Newton reflected shared intellectual concerns with 'chymistry, the transformation of materials, and the production of remedies.' These interests remained vital despite Newton's illness, which cannot now be attributed to any falling out with Fatio. Fatio found new employment as a tutor in 1694, which required him to be away from London; he travelled to the Netherlands with his pupil in 1697-8, and returned to Geneva between 1699 and 1701. Nevertheless, he remained a regular participant in conversations among Newton and his disciples: his interest in the renewed editing of the Principia and in Newton's other projects was taken for granted.

In London in 1698, Fatio set to work seeing two compositions of his own through the press: an English treatise on the exploitation of the angle of the sun's rays in gardening (Fruit Walls Improved) and a Latin pamphlet on the geometrical investigation of the line of quickest descent (Lineae brevissimi descensus), a work notable for its author's attempt to reassert a position among the front rank of European mathematicians. As such Fatio was critical of the behaviour of Johann Bernoulli and his associates for the nature of the challenge problem which they had issued in 1696, and which Newton had answered with a correct solution for the line of quickest descent. Newton had presented his work anonymously in the Philosophical Transactions (January 1697), but gave no hint about the method he had followed. He presented a construction of the solution-curve (a cycloid).

Behind Bernoulli's challenge lurked Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whom Fatio accused of having ignored Newton's priority in the invention of the calculus in his publications about this mathematical tool. At the heart of the dispute lay a broader intellectual problem that many Continental mathematicians had in accepting Newton's subordination of his method of fluxions to traditional geometrical arguments and their consequent belief that Newton had not properly mastered the intricacies of the new analysis that Leibniz had developed. On such a reading, no other mathematician in England except Newton was worthy of consideration (Fatio included). Fatio's pamphlet also treated the problem of the solid of least resistance, which Newton had solved in Book II of the Principia (1687). He wished to show that, since Newton had solved the problem of the solid of least resistance in 1687, he could equally well solve the problem (belonging to the same class) of the line of quickest descent nine years later. Mathematically speaking the two problems are similar: if you know how to solve one, then you are likely to know how to solve the other. Fatio's work therefore set out to suggest that, since he and Newton had known one another and shared mathematical work since 1687, he too rightfully belonged among the sharpest mathematicians of Europe.

Fatio's publication put the cat among the pigeons and is properly considered the opening salvo in a decade and a half of philosophical warfare between Newton and Leibniz. Although Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli were critical of Fatio's own solutions to the problem of the line of quickest descent, other leading mathematicians such as Jakob Bernoulli or Jakob Hermann were far more circumspect. They were particularly interested in the explanation of the mechanism of gravity that Fatio shared with them as part of his exchanges at this time. Fatio had presented these ideas to the Royal Society as early as July 1688, but they remained topical as Continental mathematicians and philosophers struggled to interpret the Principia. In this way, Fatio's pamphlet succeeded in reclaiming attention for his own scientific ideas, as well as going into the lists for Newton's reputation. It also showed that he could handle the most difficult problems in mathematics.

By the time of his return from Switzerland in 1701, Fatio was therefore a significant player in an international debate about the nature of the calculus and about the way in which physical effects might be transmitted so as to appear to cause action at a distance. These were also concerns looked at in the Opticks, initially in the two mathematical tracts appended by Newton to the work, and later also in the queries that were developed from Newton's theory of light in the revisions made to the Latin translation (Optice) of 1706. At the same time, Fatio re-established himself as a contact between Newton and skilled craftsmen in the London Huguenot community, as is shown by exchanges between the two men in the year of publication of the Opticks. These concerned the design of watches with a jewelled mechanism, which Newton eventually tested for accuracy in December 1704. Finally, Newton was in Fatio's debt as the recipient of a presentation copy of Fatio's own publication of 1699. It is not surprising therefore to find that Fatio was one of the very first recipients of a presentation copy of the Opticks on 11 February 1704.

Newton's gift of the Opticks to Fatio and the close reading implied by Fatio's annotations formed part of a broader pattern of gift-giving. Halley presented Fatio with a copy of the first edition of the Principia in 1687 (now Bodleian Library, Oxford, shelfmark Arch. A d.37). Fatio reciprocated by presenting his own book to both Newton and Halley. Newton responded with a copy of the Opticks.

Fatio was an attentive enough reader of the mathematical treatises appended to the book to make a small number of accurate corrections which were not in the errata. The mathematical tracts appended to the Opticks included some of Newton's most profound analysis of the quadrature of curves and of cubic curves, the culmination of work that he had begun in the mid-1660s and perfected in the mid-1690s. As such they had direct relevance to the growing public quarrel into which Fatio had pitched Newton. Fatio discussed the content of the Opticks with his correspondents on the Continent, although only after the latter had been able to read the work in Latin. His ongoing interest in solar light and 'crowns of coulours wch sometimes appear about the Sun & Moon' was the subject of a letter that Newton sent to Fatio on 14 September 1724, offering to communicate his ideas to the Royal Society.

Fatio's copy of the Opticks is largely invisible in scholarship, although its possible existence is mentioned in Charles Domson's thesis 'Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and the Prophets of London' (Yale University, 1972: p. 84). Fatio died in Worcester, where he had lived since 1717, in April 1753. Half of his effects passed to Corfield Clare (d.1790), rector of Madresfield and of Alvechurch, with whom he had lodged. The other half were bequeathed to the widow of Jean Allut, who was, like Fatio, a disciple of the enthusiastic Camisard prophets who had come to England in 1706. In April 1765, the Genevan natural philosopher George-Louis Le Sage purchased for £8 some of the papers that had been left to Clare. What remained in Worcestershire was acquired by the physician and antiquary James Johnstone (c. 1730-1802). His son, John Johnstone (1768-1836), who practised medicine in Worcester from 1793, later inherited the Opticks (and made a note of its acquisition by his father on the front free endpaper). He also owned other books and papers that had belonged to Fatio (most of which are now impossible to locate). John Johnstone became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1815 and subsequently donated Fatio's notes on the revision of the Principia to the Society's library. Two books from Fatio's library (copies of the first and the third edition of the Principia) survive in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, but they had presumably been sold by either Clare or Mrs Allut immediately after Fatio's death, since they were acquired from an Oxford bookseller in 1755. The Bodleian also owns a copy of Some Manifestations and Communications of the Spirit (London, 1730), a work associated with the French Prophets, which has annotations made by Fatio in Worcester in 1731. This book belonged shortly after Fatio's death to Sir John Van Hatten of Dinton Hall, Buckinghamshire, but in the twentieth century had an American owner before being purchased by the Bodleian. The Opticks has no direct sign of provenance after John Johnstone. It does bear one or two booksellers' marks and a price (£250/0/0) indicating that it was sold in England before 1971.

The print-run of the first edition of the Opticks is unknown. From the later records in the Bowyer ledgers for other books by Newton (including the second edition of the Opticks), it seems fair to assume an edition size of between 750 and 1,000 copies. The Babson catalogue lists 35 institutional copies of the first edition of the Opticks. Wallis lists 59 with a further two (one among the Babson copies) for a supposed second issue of the Opticks from which the mathematical treatises are lacking. ESTC gives 129 institutional holdings (two of which are in fact duplicated), without differentiating the two issues. With the use of additional databases and the consultation of individual online catalogues to confirm the status of particular copies, it is straightforward to identify at least 185 surviving copies, together with one copy (from those identified by Wallis) that was destroyed in the Second World War. Of these 185 copies, it has been possible to establish provenance data and descriptions of condition for approximately thirty-five for the purposes of comparison.

Most of these copies are bound in Cambridge-style panelled calf with blind fleurons on the boards. This may reliably be assumed to have been a publisher's binding, although the spine decoration may not always have been standard (many copies have been rebacked or otherwise altered). That said, copies in unrestored, original condition (such as Edmond Halley's copy, John Locke's copy, or the copy in the Old Library of Magdalene College, Cambridge) have identical decoration, tooling, and lettering on boards, spine, and (where present) red morocco spine label (gilt lettering: NEWTON'S | OPTICKS | &c). Very few surviving copies have extensive contemporary annotations: exceptions include the copies that belonged to Newton himself (Cambridge University Library, shelfmark Adv.b.39.4, used to prepare the second edition of 1717 [lacking title-page and all after p. 137 in Book III]; Trinity College, Cambridge, shelfmark NQ.16.198 [lacking pp. 1-17 and the mathematical treatises] and McGill University Library, Montreal, MS 46 [shelfmark QC353,.N57.1704]) or the copy in the Boston Public Library (with contemporary corrections and additions not in Newton's hand, giving cross-references to the work of his Cambridge successor, William Whiston). There are a number of copies with annotations from the later eighteenth or nineteenth centuries (e.g. that at the Senate House Library, London, with the annotations of the mathematician and biographer of Newton, Augustus De Morgan).

There are also a number of copies that can be identified with provenance at or near to the date of publication. Among these is a copy bought by Francis Cremer [presumably of Ingoldisthorpe, Norfolk (d. 1759)] for 12s. in 1704, and one of the copies formerly at the Babson Institute (now on deposit in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California), which has a manuscript price code with the date 1704. Leibniz's copy (Gottfried-Wilhelm-Leibniz Bibliothek, Hannover) was sent to him from London by John Hutton on 2 May (13 May NS) 1704 and received in Hannover via The Hague before 22 July (NS). The Opticks was published after the death of Samuel Pepys in 1703, but a copy entered his library during the period in which it was being curated by his nephew, John Jackson (before 1705). The French physician, Etienne François Geoffroy, received a copy (now in Cornell University Library), from Hans Sloane (Secretary to the Royal Society) via the Jesuit mathematician, Jean de Fontenay. Fontenay had visited London, where he presented Chinese artefacts to the Royal Society in March 1704. Geoffroy thanked Sloane for the gift in a letter of 20 January 1706 (NS) and presented a summary of the book's contents to the Académie Royale des Sciences in a series of sessions between 7 August 1706 and 1 June 1707. The first copy that can be traced as arriving in North America was given by James Peirce to the Library of Harvard College on 30 March 1706 (now in the Houghton Library).

More interesting still are copies presented to their first owners by Newton himself (none of which bear inscriptions in Newton's own hand). These include:

1. The copy now in the library of the Royal Society, presented at a meeting of the Society on 16 February 1704.

2. The copy presented by Newton to Francis Hall '[th]e beginning of March 1703' [= 1704 NS]. Since no later than 1828, this has been held by the library of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.

3. The copy presented to Edmond Halley (lot 918, Robert S. Pirie sale, Sotheby's New York 2015). This is inscribed by Halley 'Luceo' and (perhaps not in Halley's hand) 'Ex dono doctissimi Authoris'. It is in a similar binding to the copy on offer here, but with the red morocco label present. It measures 24.5 cm x 16.6 cm, so is marginally taller (but less wide) that Fatio's copy.

4. The copy given by Newton to John Locke (died 28 October 1704), now in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. It is inscribed by Locke: 'Ex dono Auctoris | Viri Doctissimi. Intigerrimi Amicissimi' and was given to Trinity in 1895. The first of the corrections in the errata is made in ink; Rr1v and Rr4r are poorly printed. It is in a similar binding to the copy on offer here, but with the red morocco label present. It is slightly taller and wider than Fatio's copy, suggesting that despite the similarities in binding there were distinctions made by the binder between larger and ordinary, smaller copies for presentation.

5. The copy (now lost) that Newton sent to the Pisan mathematician, Guido Grandi (1671-1742), accompanied by a letter dated 26 May 1704. This copy cannot be located among Grandi's books in the manuscript catalogue of his library prepared in 1769, and precise details about it are therefore unknown. The library has been part of the Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa since 1783. A copy of the 1706 Optice may be found there.

6. The copy offered at Christie's New York on 16 June 2016 (lot 131), which bears the inscription 'Ex dono Authoris Mathematicorum Coryphaei, 1703/4'.

Many of Fatio's annotations deal with errors already described on the errata page of the Opticks (where Fatio notes that he has corrected these errata in the text: "Haec Errata correcta sunt'). Most are in ink, some are in pencil. The pencil corrections, which are confined to De Quadratura, are all found in the 1711 edition of Newton's mathematical tracts and were presumably added after that date. The ink corrections are more likely to have been made shortly after Fatio was given the book, although some of them may have been incorporated from the 1706 Latin Optice, in which they also appear. There is no evidence of any communication between Newton and Fatio in the making of these corrections. The only one of Newton's copies of the Opticks to contain the mathematical tracts is now at McGill University. It contains only one of the corrections made by Fatio in pencil, but it also contains many other corrections and additions incorporated either in the 1706 Optice or in the 1711 mathematical tracts which are not in Fatio's copy of the Opticks. The errata are mostly corrected in the main body of the text in all three of Newton's copies of the Opticks. In the copy at Trinity College, these corrections are frequently not in Newton's hand, suggesting that they were made already in the printing shop. In Fatio's copy, occasional items in the errata have not been corrected in the text (e.g. the corrections for pp. 86, 93, and one of those for p. 143 in book I, pp. 11 (in fact, a mistake in the errata); pp. 96, 101 (where the wrong number is corrected by Fatio) in book II). Despite such slips, the annotations show Fatio as an attentive and mathematically literate reader of the Opticks.

This copy is the earliest witness to the publication of the Opticks and a valuable testament to the ongoing friendship and intellectual exchange between Newton and Nicolas Fatio de Duillier, a very significant figure in his own right and the first mover in the public calculus controversy. It is one of only four books known from Fatio's library and is undoubtedly the most significant book that could emerge that he owned. It is a more interestingly annotated copy of the Opticks than any of the other surviving presentation copies (including that given to Halley) or than most of the other copies (apart from Newton's own) with contemporary annotations and provenance. Of known presentation copies that cannot now be located, Grandi's would not compare with Fatio's for interest or significance, Other copies that might be presumed to have existed include that of John Flamsteed (acquired by November 1704, but unknown apart from references in correspondence) and that of David Gregory. Because the book was in English, most important Continental contemporaries of Newton (such as the Bernoullis) did not acquire it until after the publication of the Latin Optice in 1706. None of these copies, were they to come onto the market, would surpass Fatio's unless they were very heavily annotated with original material. Moreover, Fatio's copy is in good, original condition and compares very well in this respect with any other copy that is available or likely to become available.

We are extremely grateful to Scott Mandelbrote for his help in cataloguing this lot.

290

Newton (Sir Isaac) Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light, 3 parts in 1, first edition, presentation copy to Nicolas Fatio de Duillier and with his ink and pencil annotations, title printed in red and black, 19 folding engraved plates, paper flaw to part 1 p.98 with some distortion to 2 lines of text and letters supplied in ink by the printer, a couple of other printing flaws probably features of the earliest copies to come off the press, contemporary panelled calf, rubbed, joints split but firm, spine ends slightly chipped, corners worn, lacking spine label, preserved in modern silk-lined green morocco drop-back box by Shepherds, [Babson p.66; Gray 174; Wallis 174], 4to, Printed for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford, Printers to the Royal Society, 1704.

*** Highly important association copy, received by Fatio, Newton's close friend and collaborator, five days before Newton himself presented a copy to the Royal Society. The earliest known presentation copy of the only book Newton prepared for publication and saw through the press himself.

Inscribed at the top of the front pastedown in Fatio's hand: 'Ex Dono Autoris Clarissimi: Londini, Februarii undecimo, 1703/4. Nicolaus Facius.' Fatio also used the Latin form of his name in an inscription recording presentation by Newton in his copy of the third edition of the Principia (1726).

The date of presentation is of particular interest. The Opticks builds on work that Newton carried out as early as the mid-1660s and later presented in his earliest lectures as Lucasian Professor in Cambridge. His first publications in the journal of the Royal Society, the Philosophical Transactions, were on the nature of light. For much of the 1670s, he engaged in critical correspondence with English and Continental virtuosi about his findings. As he stated in the 'Advertisement' at the beginning of the published Opticks, he began to prepare a more complete work on light in about 1675. He returned to the idea of publishing this work only after the appearance of the Principia (which contained one section on optical mechanics) in 1687 had won him international fame. The manuscript was largely prepared in the period 1687-8 and 1691-2. The Scottish mathematician and Oxford Professor of Astronomy, David Gregory, saw an incomplete text when he visited Newton in Cambridge in May 1694. Newton delayed finishing the book, however, and decided to print it only in 1702 or 1703. The book was going through the press in December 1703. On 16 February 1704, Newton presented the completed book to the Royal Society, of which he had been President since 30 November 1703. The copy on offer was presented to Fatio five days earlier.

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (1664-1753) was a Swiss mathematician and natural philosopher. Educated at the Academy of Geneva, Fatio worked with Giovanni Domenico Cassini at the Royal Observatory in Paris in the early 1680s. He first came to England in 1687 and became a Fellow of the Royal Society on 2 May 1688. After the Revolution of 1688, Fatio was the most important intermediary between Newton and Huygens. Fatio regarded himself (with some justification) as being among the very few mathematicians internationally who were equipped to handle the new calculus and as being in the forefront of scientists who were trying to explain the action of gravity, the force which played such an important role in the physical explanations provided by the Principia. In the early 1690s, Fatio emerged as the likeliest person to produce a revised edition of the Principia and discussed corrections to the work with Newton, to whose manuscripts he also had access. At this time, he was one of Newton's closest confidants. The two men regularly exchanged letters (several of which remain unpublished) and Fatio advised Newton in particular about the purchase of alchemical works in French.

For much of 1693, Newton and Fatio collaborated on alchemical experiments, with Fatio conveying information derived from practitioners with whom he associated in the London Huguenot community. According to William R. Newman, who has recently produced a definitive account of the alchemical collaboration of Newton and Fatio, Newton was 'testing the ability of a vitriol to "ferment" respectively with salts of lead, tin, and copper' and fermenting iron, copper, and lead with metallic quicksilver. Exhaustion from long hours tending the furnace involved in these experiments may well have caused Newton's famous breakdown, which he discussed in letters to Samuel Pepys and John Locke in autumn 1693. Newman's work demonstrates that Fatio's involvement with Newton reflected shared intellectual concerns with 'chymistry, the transformation of materials, and the production of remedies.' These interests remained vital despite Newton's illness, which cannot now be attributed to any falling out with Fatio. Fatio found new employment as a tutor in 1694, which required him to be away from London; he travelled to the Netherlands with his pupil in 1697-8, and returned to Geneva between 1699 and 1701. Nevertheless, he remained a regular participant in conversations among Newton and his disciples: his interest in the renewed editing of the Principia and in Newton's other projects was taken for granted.

In London in 1698, Fatio set to work seeing two compositions of his own through the press: an English treatise on the exploitation of the angle of the sun's rays in gardening (Fruit Walls Improved) and a Latin pamphlet on the geometrical investigation of the line of quickest descent (Lineae brevissimi descensus), a work notable for its author's attempt to reassert a position among the front rank of European mathematicians. As such Fatio was critical of the behaviour of Johann Bernoulli and his associates for the nature of the challenge problem which they had issued in 1696, and which Newton had answered with a correct solution for the line of quickest descent. Newton had presented his work anonymously in the Philosophical Transactions (January 1697), but gave no hint about the method he had followed. He presented a construction of the solution-curve (a cycloid).

Behind Bernoulli's challenge lurked Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whom Fatio accused of having ignored Newton's priority in the invention of the calculus in his publications about this mathematical tool. At the heart of the dispute lay a broader intellectual problem that many Continental mathematicians had in accepting Newton's subordination of his method of fluxions to traditional geometrical arguments and their consequent belief that Newton had not properly mastered the intricacies of the new analysis that Leibniz had developed. On such a reading, no other mathematician in England except Newton was worthy of consideration (Fatio included). Fatio's pamphlet also treated the problem of the solid of least resistance, which Newton had solved in Book II of the Principia (1687). He wished to show that, since Newton had solved the problem of the solid of least resistance in 1687, he could equally well solve the problem (belonging to the same class) of the line of quickest descent nine years later. Mathematically speaking the two problems are similar: if you know how to solve one, then you are likely to know how to solve the other. Fatio's work therefore set out to suggest that, since he and Newton had known one another and shared mathematical work since 1687, he too rightfully belonged among the sharpest mathematicians of Europe.

Fatio's publication put the cat among the pigeons and is properly considered the opening salvo in a decade and a half of philosophical warfare between Newton and Leibniz. Although Leibniz and Johann Bernoulli were critical of Fatio's own solutions to the problem of the line of quickest descent, other leading mathematicians such as Jakob Bernoulli or Jakob Hermann were far more circumspect. They were particularly interested in the explanation of the mechanism of gravity that Fatio shared with them as part of his exchanges at this time. Fatio had presented these ideas to the Royal Society as early as July 1688, but they remained topical as Continental mathematicians and philosophers struggled to interpret the Principia. In this way, Fatio's pamphlet succeeded in reclaiming attention for his own scientific ideas, as well as going into the lists for Newton's reputation. It also showed that he could handle the most difficult problems in mathematics.

By the time of his return from Switzerland in 1701, Fatio was therefore a significant player in an international debate about the nature of the calculus and about the way in which physical effects might be transmitted so as to appear to cause action at a distance. These were also concerns looked at in the Opticks, initially in the two mathematical tracts appended by Newton to the work, and later also in the queries that were developed from Newton's theory of light in the revisions made to the Latin translation (Optice) of 1706. At the same time, Fatio re-established himself as a contact between Newton and skilled craftsmen in the London Huguenot community, as is shown by exchanges between the two men in the year of publication of the Opticks. These concerned the design of watches with a jewelled mechanism, which Newton eventually tested for accuracy in December 1704. Finally, Newton was in Fatio's debt as the recipient of a presentation copy of Fatio's own publication of 1699. It is not surprising therefore to find that Fatio was one of the very first recipients of a presentation copy of the Opticks on 11 February 1704.

Newton's gift of the Opticks to Fatio and the close reading implied by Fatio's annotations formed part of a broader pattern of gift-giving. Halley presented Fatio with a copy of the first edition of the Principia in 1687 (now Bodleian Library, Oxford, shelfmark Arch. A d.37). Fatio reciprocated by presenting his own book to both Newton and Halley. Newton responded with a copy of the Opticks.

Fatio was an attentive enough reader of the mathematical treatises appended to the book to make a small number of accurate corrections which were not in the errata. The mathematical tracts appended to the Opticks included some of Newton's most profound analysis of the quadrature of curves and of cubic curves, the culmination of work that he had begun in the mid-1660s and perfected in the mid-1690s. As such they had direct relevance to the growing public quarrel into which Fatio had pitched Newton. Fatio discussed the content of the Opticks with his correspondents on the Continent, although only after the latter had been able to read the work in Latin. His ongoing interest in solar light and 'crowns of coulours wch sometimes appear about the Sun & Moon' was the subject of a letter that Newton sent to Fatio on 14 September 1724, offering to communicate his ideas to the Royal Society.